The daughter of a Presbyterian missionary born in 1892,

Pearl not only grew up and lived in China but knew the country intimately,

inside and out. Because of her father’s missionary work, the Sydenstrickers

were quite isolated and lived primarily only among local Chinese people rather

than in a segregated world among other foreigners. Indeed, Chinese and English

were both her first languages and she learned the ways of the people around

her. China was her home.

China being her foster country, she had a unique perspective

of it that only few other foreigners could intimately understand. To say the least,

her relationship with China was always tumultuous because of the many changes

and growing pains that China experienced within her lifetime. In 1900 at the

age of eight, her family made a near escape from her hometown of Zhenjiang to

Shanghai during the Boxer Rebellion when angry boxers and the Empress Dowager

Cixi declared war and death to foreigners across the country to put an end to

foreign and imperialist influences in China. Again in 1927, her family barely

escaped out alive from Nanjing when Nationalist troops, Communist forces and

warlords turned on foreigners residing there. Hiding with a poor Chinese family

who risked their own life harboring the fugitives, the Buck’s home was looted

and the family escaped at the last possible moment when an American warship

came to rescue remaining trapped residents in the city under siege. When Pearl Buck finally left China in 1934,

perhaps she didn’t realize that she would never return to China ever again.

Political unrest and strife between Chiang Kai-Shek’s Nationalist troops and

Communist factions plagued the country along with Japan’s invasion of China and

the Second World War, likely making a return to China near impossible. The

establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 effectively closed off

China to the outside world for more than twenty years. At the height of the Cultural

Revolution in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s that reigned in Marxist reform

throughout China, Pearl Buck and her writing were denounced as imperialist by

ideologues and school children across the country. Hoping to travel to China

with American President Richard Nixon in 1972 when relations between China and

the US began to warm, it is said that Pearl Buck’s request for a visa was

personally denied by Madame Mao who hoped to succeed her husband politically.

Said to be heartbroken, Pearl Buck never again returned to her home in China.

She died the following year in 1973.

In the nearly forty years since the fateful decision that

prevented Pearl Buck from returning to her home in China, her reputation as a

friend and advocate of China has been restored. Her more famous works are

available in both Chinese and English and American and Chinese organizations

work together to honor her life in both her home and adopted countries.

Recently I had the opportunity to witness this cross-cultural collaboration to

memorialize her life and accomplishments both in the US and in China.

In search of Pearl

I first encountered Pearl Buck when I was in the 8th

grade and read a copy of The Good Earth (

I will henceforth refer to Pearl Buck simply as Pearl as I feel as if I am

writing about an old friend). Never a very avid reader, I remember being

completely hooked from the beginning of the story of Wang Lung, a poor Chinese

farmer who awakens with excitement on the day he’s going to meet and marry his

bride Olan who is a servant slave girl at the estate of the wealthy family of

the village. The ups and downs their family endures through famine,

revolutions, family fortunes and misfortunes unexpectedly enchanted the 14 year

old reader in me who never personally knew such tragedy or hardship. Pearl had

so beautifully crafted the story so that I felt I personally was witnessing the

trials and tribulations of the couple. Yet she wrote the story in simple enough

language so that I never felt like the book was unattainable or for more

educated and well-read minds than my own. After first reading The Good Earth, I slowly found a new

appreciation of books and literature and people’s life experiences through the

written word. Time and time again and

through the years, I would come back and reread The Good Earth- as a young adult and again when I moved to China

two years ago. Each time I would pick it up, I knew what I was getting myself

into and that I was reading the story to know my emotions were in check. I knew

I was reading it so I could cry and feel the sadness at certain points in the

saga. Yet still I would catch myself unexpectedly, uncontrollably and

shamefully sobbing while reading it at certain parts. Each time I have read it,

I have gained new and unique perspectives based on my own experiences in my

life at that given time.

| Pearl Buck's headstone at her home in Pennsylvania. She transformed her garden and landscaped it with bamboo and other native Asian plants to remind her of her faraway home. |

| Pearl's grave with her name Sai Zhenzhu in traditional characters. |

This past month, I finally crossed a big item on my must-see

Pearl Buck homage list. With the company of a friend, I finally visited

Zhenjiang, the hometown in China of Pearl Sydenstricker. The trip was two years

in the making. Several times over the past two years, busy schedules got in the

way of my pilgrimage to Zhenjiang. Only 20 minutes away by high speed train

from Nanjing, I was running out of excuses not to visit Zhenjiang and knew I

was just going to have to make the time.

| Exploring the network of alleys in Zhenjiang. |

| At last finding the Sydenstricker's home. |

| Pearl's childhood bedroom |

| Chang Jiang (Yangtze River) played a major role economically during Pearl's lifetime. |

| A reminder of Zhenjiang's and China's tense relationship with foreigners. |

|

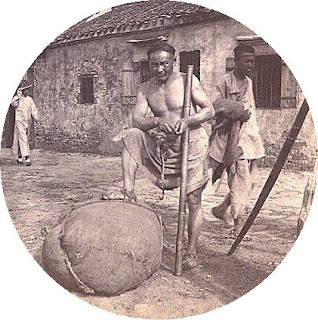

| A coolie in Zhenjiang during the time of Pearl's childhood. |

Sometimes my Chinese students ask me to recommend English

language novels for them to improve their vocabulary and to help them learn

about American culture. Perhaps they find it strange when I recommend a novel

from someone who wrote so intimately about their own part of the world. I think

younger Chinese readers will especially be touched by the careful, detailed and

loving portrayal of different aspects of Chinese life from before their time. What a wonderful gift Pearl Buck’s writing

and legacy have left not only to readers from outside of China, but to China

itself.

Pearl Buck places to visit:

In China:

Pearl S. Buck Former Residence and the Pearl S. Buck Museum

6 Runzhou Shan Lu, Zhenjiang

The museum is located right next to the residence. Both the residence and the museum are free of charge. Visiting hours of both attractions are 9 am- 11:30 and 1:30-5.

Pearl S Buck Memorial House

Nanjing University, Nanjing

Nanjing University recently turned Pearl Buck’s home during her years in Nanjing into a memorial. Pearl lived with her husband and two daughters in Nanjing from 1920 – 1933. She taught English literature at both Nanjing University and the National Central University (which is now Southeast University in Nanjing). I have yet to find and visit this location but shall update with any information I find!

6 Runzhou Shan Lu, Zhenjiang

The museum is located right next to the residence. Both the residence and the museum are free of charge. Visiting hours of both attractions are 9 am- 11:30 and 1:30-5.

Pearl S Buck Memorial House

Nanjing University, Nanjing

Nanjing University recently turned Pearl Buck’s home during her years in Nanjing into a memorial. Pearl lived with her husband and two daughters in Nanjing from 1920 – 1933. She taught English literature at both Nanjing University and the National Central University (which is now Southeast University in Nanjing). I have yet to find and visit this location but shall update with any information I find!

Pearl S. Buck Summer Villa

Lu Shan or Mount Lu

Pearl, her siblings and her parents spent many summers on Mount Lu to escape the oppressive heat in Zhenjiang at the summer villa Pearl’s father built in northern Jianxi Province. It is apparently at this summer residence where Pearl penned The Good Earth.

Pearl, her siblings and her parents spent many summers on Mount Lu to escape the oppressive heat in Zhenjiang at the summer villa Pearl’s father built in northern Jianxi Province. It is apparently at this summer residence where Pearl penned The Good Earth.

In the US:

Pearl S. Buck Residence

520 Dublin Road, Perkasie, PA 18944

In Bucks County outside of Philadelphia, this is where Pearl Buck resided with her second husband Richard Walsh and with their growing family of adopted children from 1935 until her death in 1973. Here you can visit her grave, tour the home and also learn about her work in starting the first international, interracial adoption agency and in advocating for an end to discrimination and poverty of children from Asian countries.

Pearl S. Buck Residence

520 Dublin Road, Perkasie, PA 18944

In Bucks County outside of Philadelphia, this is where Pearl Buck resided with her second husband Richard Walsh and with their growing family of adopted children from 1935 until her death in 1973. Here you can visit her grave, tour the home and also learn about her work in starting the first international, interracial adoption agency and in advocating for an end to discrimination and poverty of children from Asian countries.

The Pearl S. Buck Birthplace

U.S. 219

Hillsboro, West Virginia 24946

Born in Hillsboro, West Virginia in the hills of Appalachian Mountain, Pearl moved to China at the age of three months in 1892.

U.S. 219

Hillsboro, West Virginia 24946

Born in Hillsboro, West Virginia in the hills of Appalachian Mountain, Pearl moved to China at the age of three months in 1892.

For Further Reading:

If you can’t visit any of the Pearl Buck residences, enjoy

these books.

The Good Earth by Pearl Buck

First published in 1931, this book then went on to get Pearl Buck both a Pulitzer Prize and the Nobel Prize for Literature. Although the Good Earth itself is probably Pearl Buck’s most famous novel, it is the first of a trilogy. The other two volumes in the trilogy include Sons and A House Divided. This is a good place to start with her literature.

First published in 1931, this book then went on to get Pearl Buck both a Pulitzer Prize and the Nobel Prize for Literature. Although the Good Earth itself is probably Pearl Buck’s most famous novel, it is the first of a trilogy. The other two volumes in the trilogy include Sons and A House Divided. This is a good place to start with her literature.

Published in 2010, this biography of Pearl Buck gives intimate details about

Pearl Buck’s life in China as well as her complex relationship with the country

following her return to the US and in the following decades.

Coming of age during the Cultural Revolution, Chinese author Anchee Min was

instructed to denounce Pearl Buck in school in the late 1960’s. Years later

after having moved to the US and after being a published author herself, Min

finally read a copy of The Good Earth.

Moved by Pearl Buck’s intimate portrayal of the peasant experience in China,

Min set out to visit Pearl’s hometown and get first-hand accounts of Pearl and

her life in Zhenjiang. What came out from it was this novel which is a

fictionalized account of Pearl Buck’s life from the perspective of her

childhood and lifelong friend.